Fathers under the microscope

By Emma Proctor on 03 September 2018 Midwives Magazine

Emma Proctor measures the impact of local trust practices on screening fathers as part of the NHS antenatal sickle cell and thalassaemia screening programme.

Sickle cell and thalassaemia (SCT) are recessively inherited conditions that affect the red blood cells and are collectively known as haemoglobinopathies (Public Health England (PHE), 2018). In England, sickle cell disease affects 1000 pregnancies each year, predominantly those with west African, Caribbean, Middle Eastern and Indian ancestry (PHE, 2018). Sickle cell disease causes severe pain, anaemia, infection and chest problems (PHE, 2016).

Thalassaemia is a condition affecting the quantity of red blood cells in the body and those with beta thalassaemia major are usually transfusion-dependent for life, with additional complications associated with iron overload as a by-product of transfusion (PHE, 2016). Beta thalassaemia major affects approximately one in 27,000 pregnancies in England (PHE, 2018).

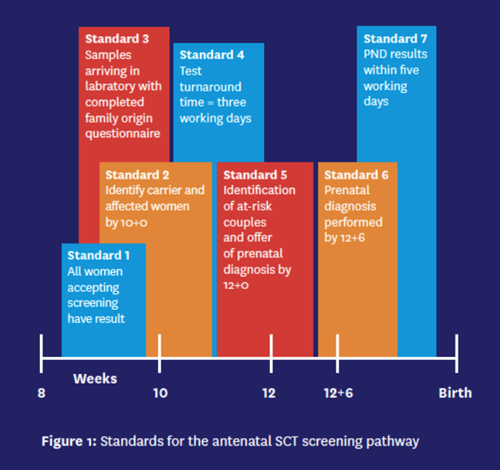

In England, the NHS offers screening to pregnant women with a subsequent offer to the father to identify parents at risk of an affected child. This enables informed decision-making regarding the pregnancy (PHE, 2017a). PHE sets the national standards for screening (outlined in Figure 1), and its 2015-16 annual data report shows that average father uptake of baby screening across the country is approximately 60%, but rates appear to be falling in low-prevalence areas (PHE, 2017b).

Aim and method

The aim of the project was to understand how variation in local pathways and processes impacts on the uptake of father screening as part of the NHS antenatal SCT programme across England.

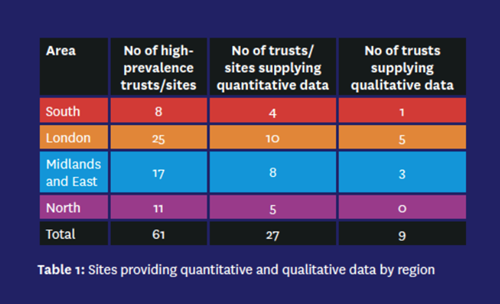

A mixed-methods study was undertaken in maternity units across England. A total of 61 SCT high-prevalence sites participated, including four large trusts with two hospital sites each. The PHE definition of a high-prevalence site is one with greater than 2% screen-positive rate for SCT carriers in the pregnant population (PHE, 2017c). Screening uptake data was collected between April 2015 and March 2016 to identify sites with high and low uptake of father screening. Data was coded numerically by geographical region to preserve anonymity.

Recorded telephone interviews were undertaken during July, August and September 2017. The interviews explored local practice in relation to the screening pathway, including pre-conceptual screening, the role and responsibility of the screening pathway, use of resources and level of training completed. In addition, the interview included a discussion of any improvements that had been made to local pathways to improve uptake, and any suggestions that the interviewee had for the future.

Ethical considerations

This study did not require health regulation authority approval because it involved NHS employees. Correspondence between the researcher and the participants of the study was through secure NHS mail or a trust email address, and no personal email accounts were used.

Trusts participating in the study were given a unique study code and were identified by the unique number only during data analysis. Information was kept on a secure laptop accessible only by the researcher and was password protected. Participants were informed that the data supplied in this study would not be used to inform their local screening quality assurance service/commissioning teams. There was no discussion of individual cases or clients, and discussion at interview remained generic to the pathway only. Where participants disclosed their place of work during interview, the name was removed when the data was transcribed. Qualitative data was supplied by the HoM at each maternity service, and signed consent was sought prior to interview.

Results and interviews

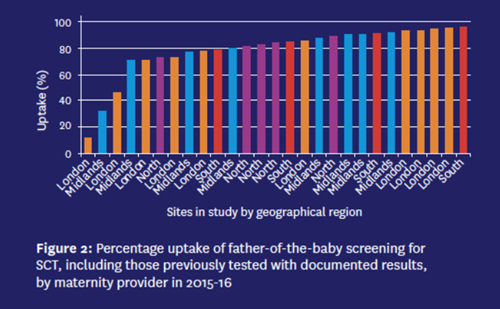

The response rate was 45% (27 out of 60). The total number of women booking for maternity care in the sample was 189,650. The total number of screen-positive mothers in the sample was 5473 (2.89% of the booking population). The rate of screen-positive mothers varied across the country and within each region, the highest in London at 8% and the lowest at 0.79% in the Midlands. The total uptake of father screening in the sample was 75.3%. Figure 2 shows that there is variable uptake of father screening across England, ranging from 11.4% to 95.7%.

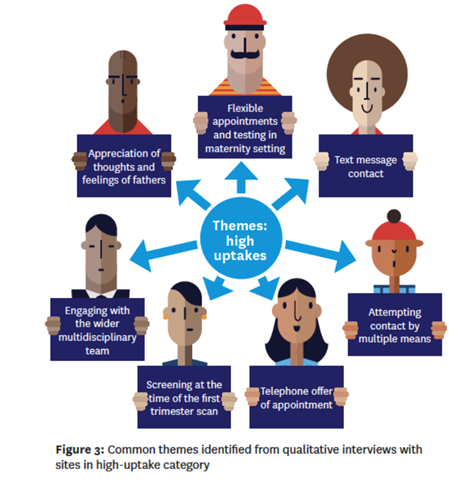

Four of the five maternity providers with the lowest uptake of father screening accepted an invitation to interview. Five providers with the highest uptake participated in the qualitative interviews. In total, nine screening coordinators or specialist sickle cell nurses were recruited. Themes identified from the high-uptake cohort are shown in Figure 3.

Low and high uptakes

Two sites with high uptake of father screening reported that they contact the woman by text message to offer screening to the father of the baby. Both reported that women are more responsive to text messages than telephone calls. Also, text messages can be beneficial to women whose first language is not English as they might not answer a phone call because of difficulty holding a conversation.

One respondent said: ‘We do try and use the phone, but occasionally nowadays because of the high incidence of nuisance calls that women receive, they won’t answer our call... I think also if there is a language barrier... sometimes they won’t pick up their phone. And if they know it is a midwife then they would do... I think sometimes people maybe when English isn’t their first language, though they can speak it, will sometimes answer a text message.’

Text messaging as a method of contacting the mother was not included within any pathways in trusts with low uptake in 2015-16.

Four out of five sites with high uptake of screening initially contacted the pregnant woman by phone with an offer to attend a face-to-face appointment for the discussion of results and requirement for father screening.

‘We would normally ask her to come in with her partner. We would suggest offering the partner some testing and we would offer a face-to-face appointment and discuss it with the partner,’ said an interviewee.

In contrast, two sites in the low-uptake group did not contact the mother by phone but sent letters. One provider who phoned the mother did not offer a face-to-face appointment, and the fourth provider phoned the mother and offered an appointment but had little engagement, reportedly due to the expansive geographical area covered and proximity of some to the hospital.

‘It is hard trying to get them to agree to come all the way into the hospital. It’s normally two or three buses for some women and can be a bit difficult, so they are reluctant to come in and have a face-to-face meeting,’ said a respondent.

All five interviewees in the high-uptake category stated that testing of the baby’s father would be completed in the maternity department by the screening coordinator. A majority said that this reduces the chance of error – for example, wrong details entered on the blood label or samples becoming misplaced and therefore not tested. Two sites offer testing at the weekend with an MSW: ‘He comes to us, we personally do it. We find we get less mistakes that way,’ said a respondent.

‘We have a little room that we can use, a quiet room, so often we will talk to them in there. And then we have a phlebotomy room... it is always with somebody who can actually answer their questions just in case.’

In the low-uptake category, two of the sites offered father screening in the pathology department only, with a phlebotomist.

All five respondents from the high-uptake category stated that flexibility was the key to screening men, with some reporting that men have difficulty in attending for testing during normal working hours: ‘Offering them a specific clinic day doesn’t always work. You have to offer flexibility, especially in order to get the man.’

In contrast, three of the four trusts in the low-uptake category only offered screening during working hours on Monday to Friday. The fourth site offered screening three days a week during working hours.

Although midwives prefer to screen the fathers before the first trimester scan between 11+2 and 14+1 weeks’ gestation, as a final resort the screening midwife will endeavour to undertake father screening at the same time. Three sites with high uptake reported that they find men are often in attendance at a scan appointment, sometimes even returning from abroad in order to attend.

Four out of five interviewees in the high-uptake category attempted to contact women and fathers by multiple means including phone, letter, GP and community midwife.

One interviewee said: ‘The secret is to keep going with people. Even though it is well outside the time limit of getting people tested, I still want to get the man in – so I will keep going with him.’

In contrast, three out of four providers in the low-uptake category sent a second letter to the mother if there was no response to the first. If the mother did not make contact, there was no follow-up.

Conclusion

The study shows variation in local trust practices and identifies several themes that correlate with uptake of father screening. SCT disproportionately affects ethnic minority groups; therefore, pathways should be tailored accordingly to ensure equity of access. Under the Health and Social Care Act 2012, commissioners and providers of NHS screening programmes are responsible for ensuring that they are implemented in such a way to reduce health inequalities and focus on ensuring equity of care for those with predefined ‘protected characteristics’ such as age, race, religion and sexual orientation (UK Government, 2012).

As the study sample represents nearly half of the high-prevalence trusts in England, the findings of the study provide valuable insight into processes across the country. It is hoped that the findings of this study are used to prompt providers to review current pathways and seek to strengthen processes where performance is low. This type of study could be replicated in other parts of the UK.

Emma Proctor is senior quality assurance advisor, Screening Quality Assurance Service at Public Health England